“’Tis said the soul of mortal man recoiled

To view Black Annis’ eye, so fierce and wild…”

— Lt. John Heyrick, 1797

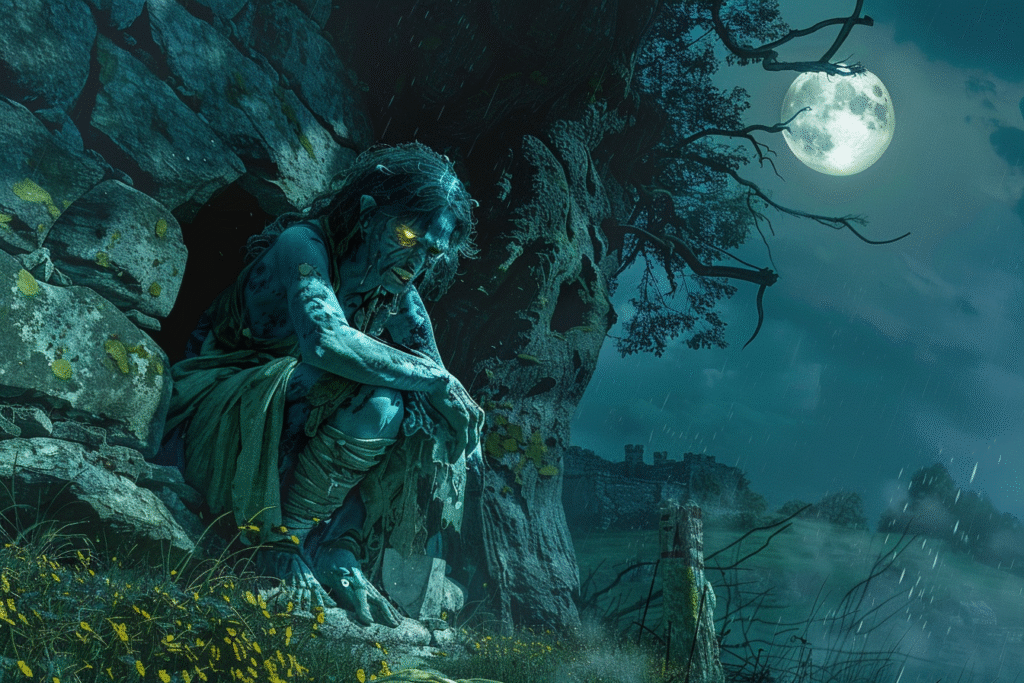

In the shadowed folklore of Leicester, few names conjure as much dread as Black Annis. A monstrous figure said to haunt the Dane Hills, she was described as a one-eyed, blue-skinned hag with iron claws, yellow fangs, and a thirst for flesh. But where did this legend come from — and is there any truth behind the terror?

The Legend of Black Annis

Black Annis was believed to dwell in a cave carved by her own iron claws in Dane Hills, west of Leicester. She would snatch children and lambs from the surrounding countryside, devour them, and hang their flayed skins from the branches of an old oak tree outside her cave.

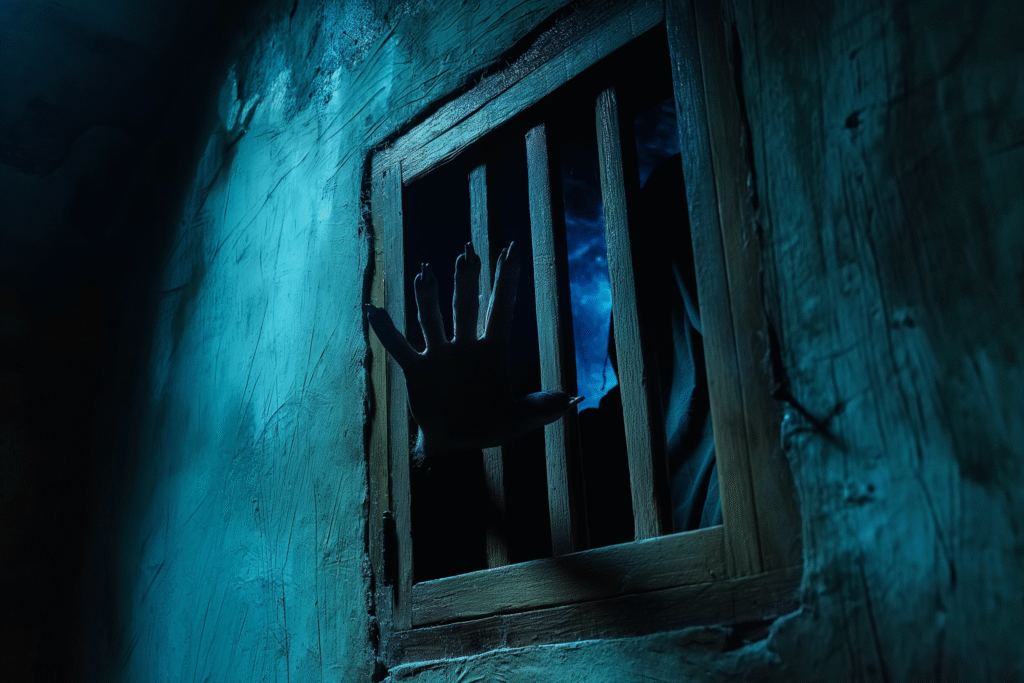

She was said to visit homes during the night, tearing children from their beds — which some believe explains the unusually small windows found in old Leicester cottages. Small enough to allow only one arm in at a time, giving children a better chance to escape her grasp.

When she shrieked, the townspeople would rush their children indoors, cover the windows, and place protective herbs around them. But the most chilling warning was said to be the grinding sound of her teeth echoing through the trees — a sign that Black Annis was near.

Real Places, Real History

While it may sound like pure folklore, many of the story’s physical elements were once real.

- Her cave and oak tree existed — though the cave has since been filled in, and the tree long gone.

- The site where she supposedly lived is now occupied by a home known as Black Annis’ Bower.

- Some accounts even claim her cave once connected to Leicester Castle through a hidden tunnel.

In the 1800s, local historian William Kelly recalled visiting the site as a child:

“On my last visit to the Bower Close… the mouth of the cave was closed, but in my school-boy days it was open… about seven or eight feet long by four or five feet wide, with a ledge of rock for a seat on each side.”

Who — or What — Was She?

1. Agnes Scott — the Anchoress

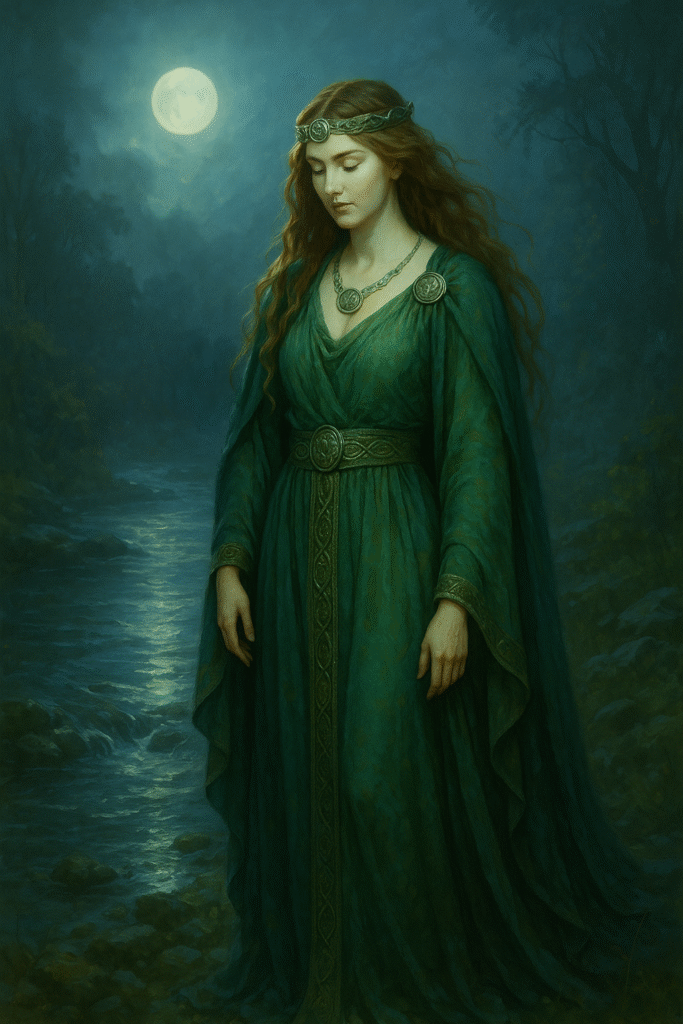

Historian Ronald Hutton proposed that Black Annis may have been a distorted memory of a real historical figure: Agnes Scott, a medieval anchoress who lived in Leicester and died in 1455. According to tradition, Agnes chose a life of deep religious isolation in a cave located in the Dane Hills — the very place where Black Annis was later said to dwell.

An anchoress (or anchorite, if male) was a religious recluse who, during the medieval period, withdrew entirely from the world to devote her life to prayer and contemplation. Often, anchoresses were literally walled into a small stone cell or cave, sometimes attached to a church. They lived in spiritual solitude, cut off from society — though occasionally they would offer spiritual guidance to passers-by through a small window.

The practice was not uncommon during the 12th to 15th centuries in England. It was widely respected, and many women who became anchoresses were revered for their piety. But after the Reformation and the rise of Protestantism, attitudes began to shift. The public grew more suspicious of secluded religious figures, particularly women. They were sometimes cast as strange, fanatical, or even dangerous.

Some folklorists believe that Agnes’ story may have been twisted over time — her cave becoming the dark lair of a flesh-eating hag, her solitude interpreted as secrecy, and her spiritual austerity warped into something witchlike. As Protestant England distanced itself from Catholic mysticism, the once-holy anchoress may have been rewritten into a monster that haunted the very hills she once prayed in.

There is no historical evidence to suggest that Agnes Scott was in any way violent or dangerous. But folklore doesn’t always need facts — only a compelling story and fertile ground for fear. And so it’s possible that Black Annis is not a demon or a goddess, but a distorted echo of a woman who once sought peace in a cave on the edge of Leicester.

2. A Forgotten Goddess

Others trace Black Annis to ancient mythologies — suggesting she may be a folkloric echo of various dark maternal goddesses once worshipped across Europe and beyond. While no single deity lines up perfectly with her image, several share symbolic traits: death, winter, darkness, devouring motherhood, and transformation.

Here are a few possible roots:

- The Gaelic Cailleach Bheare: An ancient winter crone goddess, the Cailleach was believed to rule the dark half of the year. Often described as an old, withered woman with blue or black skin, she created landscapes with her hammer and controlled the weather. Like Black Annis, she was feared, respected, and deeply tied to nature’s cycles.

- The Irish Danu: The mother of the Tuatha Dé Danann, Danu represents fertility, wisdom, and the primal forces of nature. Though not malevolent, her role as a life-giver and mystical mother connects loosely to Black Annis as a corrupted maternal figure — nurturing turned into devouring.

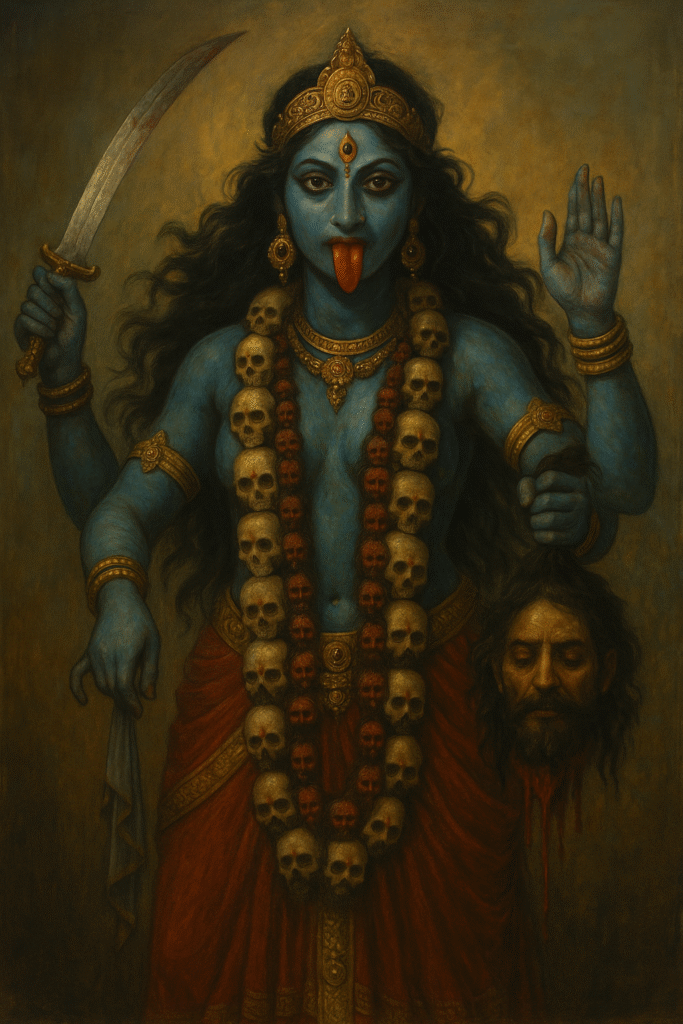

- The Hindu Kali: One of the most often cited parallels. Kali is a fierce goddess of destruction and rebirth. She is frequently depicted with blue or black skin, long wild hair, fangs, and a belt of severed heads or arms — a visual echo of Annis’ childskin belt. Kali is complex: terrifying yet protective, a destroyer of evil but frightening to behold.

- The Greek Demeter (and her darker aspect, Hecate): Demeter is the goddess of harvest and motherhood, but when her daughter Persephone is stolen by Hades, her grief turns her into a symbol of death and barrenness. Hecate, associated with magic and crossroads, may also reflect the witch-like transformation of nurturing goddesses into night-dwelling figures like Annis.

- The Mesopotamian Labartu: A demonic figure feared for harming infants, Labartu was said to prowl at night and snatch children from cribs — a direct parallel to Annis’ child-snatching reputation. Labartu may have influenced later European fears around witches and monsters who prey on the young.

- The Egyptian Neith: A warlike creator goddess, often associated with both life and death. Some depictions show her bearing weapons or weaving the fabric of reality. Though more abstract, Neith’s dual nature — creator and destroyer — echoes the blurred lines between divine and monstrous seen in Black Annis.

It’s unlikely Black Annis evolved directly from any one of these deities. Instead, she may be a folkloric collage — a convergence of ancient fears and archetypes passed down through oral tradition. As older goddesses lost their temples and were vilified or forgotten, their features may have been twisted into monstrous legends meant to warn, frighten, or control.any dark maternal figures, twisted over centuries into a child-snatching hag.

Cat Form: Black Anna

One of the most curious aspects of the legend is that Annis wasn’t always human in form. Some say she also took the shape of a huge black cat named “Anna,” capable of moving unseen through tunnels beneath Leicester.

Tradition once included a grim Easter ritual known as a drag hunt, where townsfolk dragged a dead cat soaked in aniseed from Black Annis’ Bower to the mayor’s house — supposedly to banish winter and mark the coming of spring. The practice died out in the 18th century, but its legacy lingers.

Modern Sightings

Despite her cave being long buried, stories of Black Annis persist. As recently as 2005, she was reported near St Mary de Castro Church and the remains of Leicester Castle. Locals still claim to hear her shrieks.

Separately, Leicestershire has reported up to 80 sightings of a large black panther-like creature. Some speculate this could be “Anna” — Annis in her feline form, continuing her ancient patrol.

Cultural Interpretations and Legacy

Black Annis has transcended folklore, influencing literature and popular culture. She has appeared in various works, including:

- Victorian Melodramas: In the 19th century, Black Annis featured in plays like Black Anna’s Bower, or The Maniac of the Dane Hills, portraying her as a malevolent figure akin to the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

- Modern Literature: Authors have drawn inspiration from her legend, incorporating elements into horror and fantasy narratives.

- Local Traditions: The tale of Black Annis continues to be a part of Leicester’s cultural heritage, with references in local festivals and storytelling.

Why These Legends Survive

Legends like Black Annis don’t survive by accident — they adapt, evolve, and reflect the fears of the cultures that carry them forward. While she may have started as a misunderstood anchoress, or a whispered echo of forgotten goddesses, Black Annis endured because she embodied something people recognized across generations: the dark shape in the woods, the danger of nightfall, the unknown beyond the window.

In medieval England, she was a cautionary tale — warning children to behave, stay close to home, or fear the consequences. To parents, she gave shape to the unspoken terror of losing a child. As spiritual ideas changed, the image of Annis changed too — growing darker, more pagan, more monstrous — yet still familiar.

She also filled a need. Every culture seems to invent its own “bogeywoman”: a supernatural enforcer who punishes the wicked or unwary. In a world where law and order were fragile and the wild crept close to town, having a hag in the hills made sense. She served as both a story and a shield.

But there’s something deeper at work. People are drawn to the liminal, to the edge spaces where myth and history blur. Black Annis lives in those spaces. She may never have existed in flesh and blood, but she exists in stone (the cave), in literature, in warnings passed from parent to child. That makes her real enough.

Even now, in a world of electric light and satellite maps, we cling to the dark. We retell these stories not because we believe every word — but because we recognize the feeling beneath them. And because a part of us still listens… when the wind howls across the hill.

Conclusion

Black Annis might be myth, might be memory, or might be something else entirely. A warning, a witch, a goddess, a grief-stricken spirit — her story is stitched from shadows and belief. Whether she ever walked Dane Hills or not, her legend continues to haunt them.

And in those quiet moments, just past dusk… you might still hear the grinding of teeth on the wind.

Sources & Further Reading

This post was informed by historical texts, folklore analysis, and modern interpretations. For readers who wish to explore further, here are the key sources:

- Heyrick, John – Black Annis’s Bower (1797). Poetic description and earliest literary mention of the hag.

- Ronald Hutton – The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Billson, Charles James – County Folklore: Leicestershire & Rutland. The Folklore Society, 1895.

- Wikipedia: Black Annis – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Annis

- Black Annis – Blockforest Bestiary – www.blockforest.co.uk/blogs/the-bestiary/black-annis

- Art of Black Annis – Wyrd Words & Effigies – www.wyrdwordsandeffigies.com/2019/07/04/art-of-black-annis

- British Folklore Archive – https://www.britishfolklore.com/black-annis-bower

- White Dragon Pagan Journal – www.whitedragon.org.uk/articles/blackann.htm